Why does Jesus make discipleship so hard in Luke 9?

The lectionary reading for Trinity 2 in Twelvemonth C is Luke 9.51–62. Information technology consists of a brief narrative of rejection of Jesus, following by a collection of three sayings about the challenge of discipleship—but the significance of this passage too derives from its place within Luke's overall narrative.

The lectionary reading for Trinity 2 in Twelvemonth C is Luke 9.51–62. Information technology consists of a brief narrative of rejection of Jesus, following by a collection of three sayings about the challenge of discipleship—but the significance of this passage too derives from its place within Luke's overall narrative.

Luke 9.51 signals the beginning of Luke'southward key 'journey' narrative in his gospel, which continues until Jesus' inflow on the outskirts of Jerusalem in Luke 19.44 at the moment of Cloak Sunday (in the other gospels Palm Sunday; there are no palms or branches mentioned in Luke). Luke doesn't appear to be telling us anything literal or historical almost Jesus' journeying, since many of the geographical references within this narrative are either rather vague, or in fact don't really make sense; for example, long afterward Jesus leaves Galilee and enters Samaria in this reading, we read in Luke 17.11 that he is journeying 'through the region between Galilee and Samaria'. (Joel Dark-green, NIGTC commentary on Luke, p 398)

The focus, and so, is on journeying equally a way of understanding what it ways to exist a disciple of Jesus. Right at the beginning we have heard that the 'dawn from on high' will break upon u.s. to 'guide our anxiety into theway of peace' (Luke 1.79), and in Acts we larn that those in the early Jesus movement were known as people of 'the Way' (Acts 9.2, xix.ix, 23, 22.4, 24.14, 22). The ii disciples in Luke 24 meet Jesus on theway to Emmaus, and in this section discipleship is summarised as following Jesus on the journeying he is taking. But this journey is not just about the process; it also focussed on the destination: Jerusalem. This is nonetheless another attribute of the focus on Jerusalem in Luke'southward gospel and in Acts, the fundamental place in God'due south actions from which the gospel then goes out to all the world.

The journeying to Jerusalem is a new exodus, by which Jesus forges a redemptive path to the glory of the Father. The style of Jesus becomes paradigmatic for Jesus' followers… (Mikeal Parsons,Paideia commentary on Luke, p 163).

The material in this long section does include an business relationship of Jesus' mighty words and deeds—but the primary focus is actually on Jesus's words, his didactics, and in detail his parables. Much of the material unique to Luke is in this department, including the parables of the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son and the rich man and Lazarus, and, as elsewhere in Luke, the overall shape is advisedly structured, with 12 parables before and 12 parables later the central parable of the wedding guests in Luke xiv.7–xi (Parsons, p 164). This in turn highlights a consistent theme in Luke, which was offset expressed in the Magnificat: the great reversal, past which those included get excluded and vice versa, the rich get poor and the poor blest, the proud humbled and the humble exalted.

Although many English translations begin our passage with language of 'the time approaching', Luke's language really talks of the 'days being fulfilled'. This implies a sense non merely of fourth dimension passing, but also the fulfilment of prophetic anticipation. This could be understood every bit a reference back to the anticipations of the nativity narratives in the gospel, merely besides a sense that this is the fulfilment of the longer purposes of God fix out in the scriptures of our Old Attestation. Subsequently all, earlier in this affiliate, in the Transfiguration, we have heard the (uniquely Lukan) language of Jesus completing his 'exodus' in Jerusalem; and when his journey has been completed, he explains to those on the road to Emmaus what 'Moses and all the prophets' say virtually him (Luke 24.27).

The fulfilment will be achieved by Jesus being 'taken upwardly'; English language translations add the qualifier 'to sky' by way of caption. The discussion here just occurs at this point in the New Testament; although it might seem vague at first, it appears to exist i of several allusions to the story of Elijah, and his being taken up to heaven in 2 Male monarch two.x–11. Luke is quite clear that the Ascension marks the completion of Jesus' own ministry building, which is then connected by the apostles once the Spirit has been poured out—so we have (as typical in Luke) an early on anticipation of how the whole narrative is shaped and ended.

Jesus so 'sets his face to go to Jerusalem', a (Semitic?) metaphor for resolute determination. Again, ETs tend to translate this colloquially, though this ways that we might miss the way that this phrase percolates through the post-obit verses: in the side by side verse, he sends messengers 'earlier his face'; the Samaritans reject him because 'his face was going to Jerusalem'; and the 72 are sent out 'before his confront' in Luke 10.1.

The rejection by the Samaritans assumes knowledge of the historical animosity between Samaritans and Jews, an assumption that is revisited in Jesus' didactics about loving i's neighbour in the next chapter. That animosity did lead to bodily violence, which makes the question of James and John less surprising—and their mention of calling downwardly fire equally a course of sentence is another allusion to the Elijah narrative, in which he calls down fire on Mountain Carmel in one Kings 18. But inside Luke'due south narrative, it highlights how far the disciples have still to go in their understanding of Jesus and his ministry; though Luke does indeed focus on issues of power, the ability of Jesus is used in quite a dissimilar way. Jesus' willingness to accept the rejection of the village, and move on to somewhere that volition take him has already been seen in his willingness to leave the Gerasene region in affiliate 8, and anticipates his instruction to the 72 in chapter 10.

The iii sayings of Jesus that follow take the form ofchreiae, useful sayings included to make a point, often gathered together in the context of teaching material, in which a brief maxim is attributed to someone in the context of discussion with another. Luke is one time more than demonstrating his knowledge of ancient literary conventions.

The first 2 of these exchanges is establish in the other synoptics, simply the 3rd is institute in Luke lone. The three are bundled advisedly, and then that the first and third involved a person offering to follow Jesus, but wanting to qualify their delivery, whilst the middle ane starts with Jesus' own claiming or invitation to follow.

In response to the apparent willingness of the offset person, Jesus highlights the cost and inconvenience of beingness a disciple; it involves embarking on a journey which will involve being unsettled and experiencing rejection—precisely as Jesus himself has but experienced. In the 2nd proverb, it is Jesus who takes the initiative, just the respondent points out the important commitments he has which might limit his ability to follow. There does not announced to be any specific Mosaic command to be responsible for burial one's parents, merely this could certainly be seen every bit fulfilling the control to 'laurels your father and mother', and there would at to the lowest degree be a social expectation of this duty. But Jesus now adds that following him might not only be inconvenient; it might also involve disregarding mutual social conventions, and hazard causing offence. His saying here is oft interpreted as significant 'allow the [spiritually] expressionless coffin the [physically] expressionless', in other words, leave these conventional responsibilities to those who take not taken upwardly the demanding invitation to follow Jesus as disciples. Joel Light-green (p 408) notes that the Jewish practise of interment followed by reburial of basic in an ossuary would allow a more literal interpretation: let the dead (already in the tomb) bury the other expressionless who arrive later on them. This is, of course, literally incommunicable, but makes the similar bespeak that these mundane duties cannot be allowed to distract from the demands of following him.

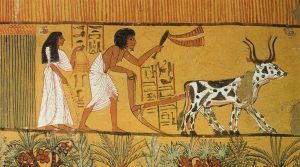

In the third proverb, Jesus is quoting a well-known proverb in the ancient world which is based on the real demands of ploughing a field, and serves to summarise the message of the previous two. If you are ploughing a field with oxen, then (as with riding a bicycle, or driving a machine, at least in the early stages) you lot need to accept your focus ahead on where you lot are going in club to plough a straight furrow. If you get distracted, and wait around or to one side, the furrow you plow will as well veer to the side as you fail to steer the squad in a straight line. This metaphor then connects dorsum to the opening verse, where Jesus metaphorically sets his sights on Jerusalem, and will not allow anything to distract him from his goal. Jesus is ploughing his ain true-blue furrow in line with the purposes of God.

So much for the details of the texts; what we are left with is a bigger question nearly why Jesus makes discipleship and so hard. If his aim, in his ministry building, was to make the grace of God known, and to invite as many equally possible in, why does he appear to put obstacles in the fashion of those who seem to want to follow, even if that is in a qualified mode? If God 'wants all people to exist saved' (1 Tim 2.4), why does Jesus make it so hard? (Proverb that 'all' here simply means 'all kinds of people' is a bit of a poor cop-out.)

Kickoff, information technology is worth noting that the thought that the kingdom of God is difficult to enter is a consequent theme of Jesus' teaching, which nosotros observe in the language of the 'narrow gate' in Matt 7.14 and the 'eye of the needle' in Matt 19.24 and parallels. Jesus is not simply in the business organisation of creating an inclusive social community, where all belong and are included in order to make them experience amend; he is concerned with inviting people into the demanding journey of inbound and growing in the kingdom of God, because that lone is the mode of life. The journey is demanding because it is a journey with Jesus, and he has followed this demanding path himself.

Secondly, the idea of refusing to conform to social norms becomes a key effect of discipleship once this Jewish gospel begins to make its home in gentile culture. We alive in a world where religion and social convention notwithstanding do have some connections, but don't go paw-in-glove every bit they did in the ancient globe. To pass up to worship the pantheon of the gods was to adventure causing social offence, and would fifty-fifty bring economic hardship, since practising your trade usually depended on this element of social conformity. We see this throughout Acts, and we find it as the issue backside a number of ethical discussions in Paul. Nosotros need to read the evidently 'bourgeois' social ethics of the NT letters in the context of this issue.

Thirdly, we need to reflect on the human relationship between Jesus' obvious attractiveness to the crowds forth with these challenging statements. There was conspicuously something compelling and inviting in Jesus' ministry building, in the way he responded to people with dignity and compassion, which meant that people of all backgrounds were drawn to him. I wonder if it is only when people observe the gimmicky church similarly attractive that nosotros are gratuitous to brand similarly enervating statements—and of course we need to model living out the reality of these demands ourselves.

Lastly, it is worth noting that including these challenges is not something nosotros find easy, or for most of us comes naturally. But it appears to be a vital role of healthy preaching and teaching that leads to healthy church growth, particularly amid men. The invitation of Jesus is an invitation to healing and wholeness, forgiveness and community, merely information technology is too an invitation to claiming and adventure, and to commence on a journey whose destination might well be unexpected and surprising.

If y'all enjoyed this, practice share information technology on social media, perchance using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is washed on a freelance basis. If you lot accept valued this mail, would you considerdonating £1.20 a calendar month to back up the production of this web log?

If you enjoyed this, practise share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this mail, you can make a unmarried or echo donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the post, and share in respectful debate, tin can add existent value. Seek get-go to sympathize, then to be understood. Brand the almost charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate equally a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

stricklandhourson.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/why-does-jesus-make-discipleship-so-hard-in-luke-9/

0 Response to "Why does Jesus make discipleship so hard in Luke 9?"

Post a Comment